Andre Agassi and Andrei Medvedev had spent the spring of 1999 smiling slyly and waving to each whenever their paths crossed. While Andrei the Russian was playing some of the best tennis of his career, Andre the American could take more than a little credit for his success.

That April in Monte Carlo, Agassi had come across Medvedev drinking himself into a stupor at a bar after a painful defeat. The 24-year-old Medvedev told Agassi he was through, he was old, he couldn’t play “this f---ing game anymore.”

Agassi, as he recounted in his autobiography, Open, sat down and talked him out of it.

“How dare you,” Agassi said. “Here I am, 29, injured, divorced, and you’re [complaining] about being washed up at 24? Your future is bright.”

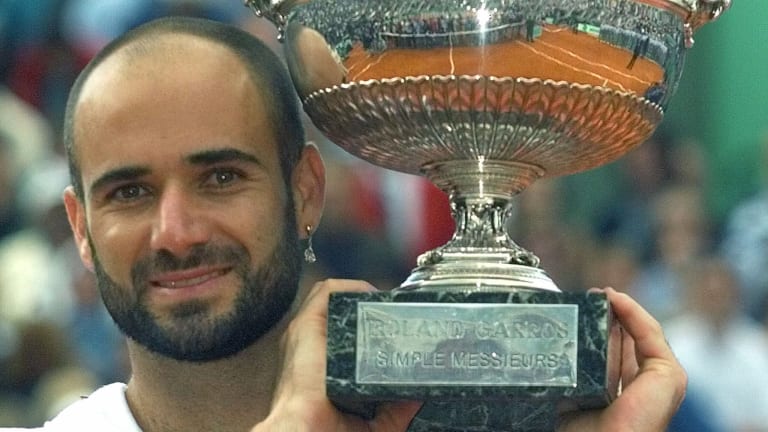

Medvedev asked for a few tips, and Agassi obliged. Whatever he said worked. Medvedev spent the next month “on fire,” as Agassi put it. Yet now Agassi realized that he may have done his job a little too well. He had reached the French Open final for the first time in eight years; it was the only Grand Slam he had never won. But to do it, he would have to beat Andrei the Russian.